Introduction. The original surgical technique that called kidney transplantation, as a treatment of choice in patients with end stage renal disease (ESRD), was first introduced in the year 1950. From that time up to now, improvements in the erea of kidney transplantation are due to refinement in the technical quality of the surgery and developments in the immunosuppressive regimen [1, 2]].

Open procedure in the right iliac fossa in most occasions is still the gold standard method of surgery. Technique regarding to vascular anastomosis suggested by Carrel in 1902 and the implanation in the iliac vessels by Kuss in 1951 [3]. Vascular and ureteric anastomosis are the basic technique in transplantation of a kidney, but vascular anastomosis of a renal artery to the external or internal iliac artery and the renal vein to the external iliac vein declared as the critical part associated with this procedure [4, 5].

However, still there are concern regarding to, preference of end-to-side anastomosis to the external iliac artery or original end-to-end to the internal iliac artery anastomosis.

The technique that has been assumed since 1950 is the anastomosis of renal vein first followed by anastomosis of the renal artery. By this approach, the rates of complications associated with early thromobosis and late stenosis of renal vessel were reported up to 6 and 23% respectively. In 1993 Sutherland et al., confirmed that end‐to-side anastomosis to the external iliac artery is the preferred method to the original end‐to-end internal iliac artery anastomosis.

Another single center study showed that anastomotic technique for transplantation of kidney based on first artery and then vein (FASV) was associated with low rates of early post-transplant vascular and urological complications when compared to the conventional vein first (FVSA) vascular anastomosis [4–8]].

Other factors that could affect transplant outcome could be mentioned as; strategy of gaining for a suitable donor, time, in situ perfusion, graft conservation solution, obtaining aortic cuffs and an extention of the right renal vein using the inferior vena cava [8]. In addition the relative contribution of donor versus other factors on clinical outcomes is also unknown [9, 10]]. Early and late acute rejection can occur less than and after three months after kidney transplantation respectively. Acute rejection could be correlate to a reduce in graft survival. In addition the incidence of acute rejection could be associated with a synergistic effect of donor-specific antibodies [11–13]].

Another most common cause of injury to the transplanted kidney is acute tubular necrosis (ATN) that is responsible for approximately 90% of acute renal kidney failure episodes occurring within the first few weeks following renal transplantation. The pattern of injury that defines acute tubular necrosis includes renal tubular damage and death. This phenomenon is observed in 34% of cadaver transplant recipients and 9% of those with live donor kidneys [14–19].

As published articles regarding to surgical vascular anastomotic and its’ correlation with clinical outcome are limited, therefore this study aims to investigate the preference (FASV or FVSA) and performance (end-to-end or end-to-side) with early clinical outcome in kidney transplant recipients in Isfahan/Iran.

Methods. A full descriptive access to 260 kidney transplant recipients records’ in a tertiary hospital; Khorshid, Isfahan/Iran was achieved. The study was conducted to Isfahan Kidney Transplant research Center (IKTRC) and was approved by the institutional review board (Ethics Code No. 296013). Data for each individual kidney transplant recipients’ included; age, gender, date of; (admission, transplantation, discharge), anastomosis performance time, cold ischemia time, donor (relative or non-relative, living or cadaver), preference of vessel anastomosis (FASV or FVSA), preference of arterial anastomosis (as end-to-end to hypogastric artery or end-to-side to common or external iliac artery), Hematoma, thrombosis of artery or vein, evidence for acute tubular necrosis (ATN) in addition to the clinical and biochemical variables were distinguished. To ensure the consistency of data, all investigators (T F, SH A, T Z) involved in data collection projected to prior training meeting for agreement on how to complete the data sheet. To ensure the accuracy of such report all content of medical records’ from the first page to the last page was studied with authors and the important information was noted. Furthermore, two senior investigators (TF and TZ) independently reviewed the collected data before analysis for accuracy and reliability. Hematoma and thrombosis have been confirmed on sonography basis. Acute tubular necrosis were convinced on a clinical basis by a physician. In agreement with previous published report a biopsy was only performed when there was suspicion of an entity other than acute tubular necrosis causing acute kidney injury [19].

Statistical Analysis

All data were noted in D-Based and analysed by SPSS. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and all other clinical characteristics of participants. The correlation between variables was determined by the Spearman rank order and Pearson regression analysis. When the data were not normally distributed and equal variances among groups could not be assumed, Mann-Witney and Kruskal Wallis were used. The association between normally distributed quantitative variables were assessed using ANOVA and Independent sample T-Test and for qualitative variables chi-square. A p value of ≤0.05 was considered as significant.

Results. With a minimum of 16 and a maximum of 72 years, the mean±SD age in the total population was 45.0±13.6 years. There was not any significant difference (p=0.89) in the age of the males when compared to the females (n=84; 45.0±13.6 versus n=176; 45.0±14.2 years) respectively. The mean hospital length of stay (LOS) was 11.7 (± 5.8) day with a minimum of 7 and a maximum of 56 day. In the 20%, the LOS was16-30 and in 1 recipient was 56 day. The mean anastomosis time (minute) was 50.7 (± 16.5) with a minimum of 20 and a maximum of 120. The mean cold ischemia time (minute) was 74.9±24.1 (Min 30; Max 170). The kidney was obtained from relative (n=3) and deceased donors (n=86).

As shown in Figure 1, anastomosis technique for transplantation of the kidney was based on FASV versus FVSA in 209 versus 51 cases concurrently. Anastomosis preferenace regarding to end-to-end versus end-to-side was in 172 versus 88 cases and anastomosis to external iliac versus common iliac was 49 versus 39 cases (Figure 2).

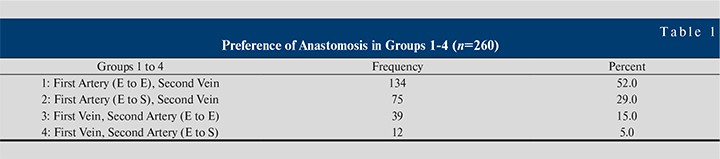

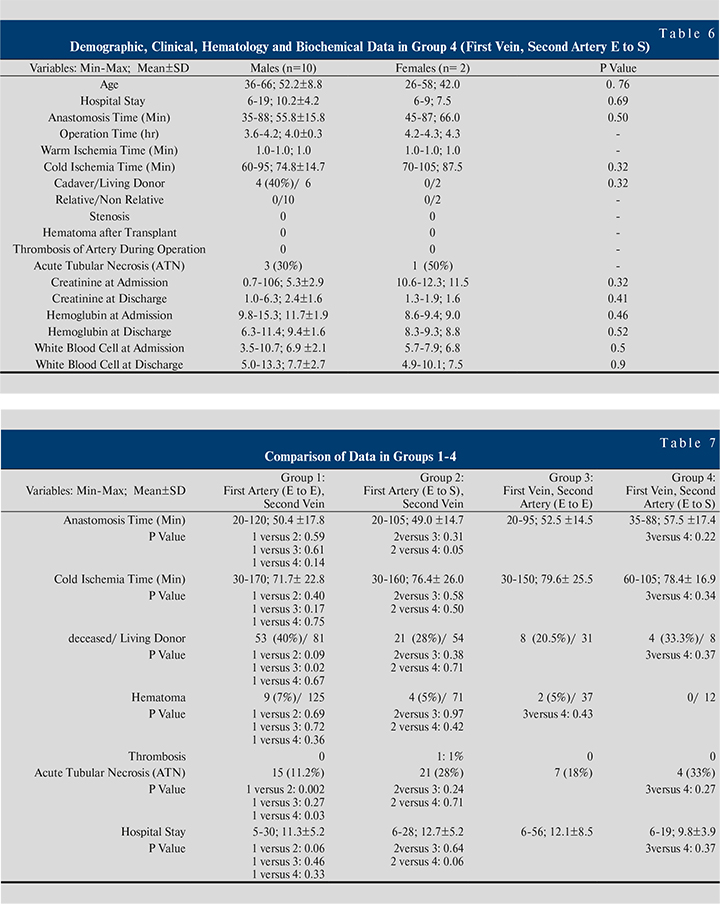

Table 1 shows the preference of anastomosis in groups 1–4. There were group 1 (FASV with end-to-end; n=134), group 2 (FASV with end-to-side; n=75), group 3 (FVSA with end-to-end; n=39), group 4 (FVSA with end-to-side; n=12).

Hematoma was reported in 15 (6%) that in 7 (47%) occasions, the recipients received kidneys from cadaver donors. Acute tubular necrosis (ATN) reported in 47 (18%) that in 20 (43%) occasions, the recipients received kidneys from cadaver donors.

Hematoma was reported in 15 (6%) that in 7 (47%) occasions, the recipients received kidneys from cadaver donors. Acute tubular necrosis (ATN) reported in 47 (18%) that in 20 (43%) occasions, the recipients received kidneys from cadaver donors.

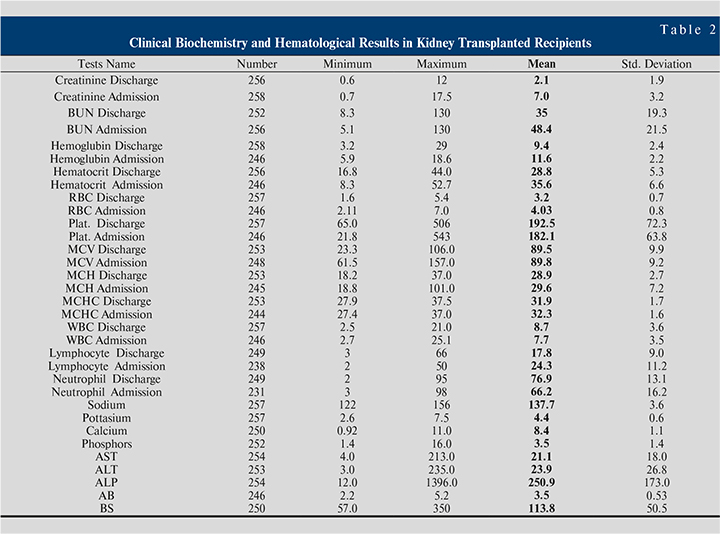

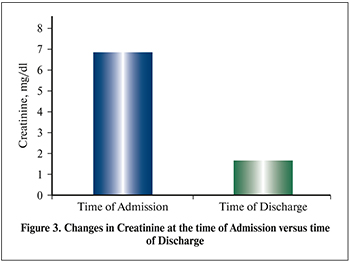

Table 2 shows clinical biochemistry and hematological results in kidney transplant recipients. Changes in mean creatinine (mg/dl) at the time of admission and time of discharge (Figure 3) were 7.0 versus 2.1 (p=0.00) respectively.

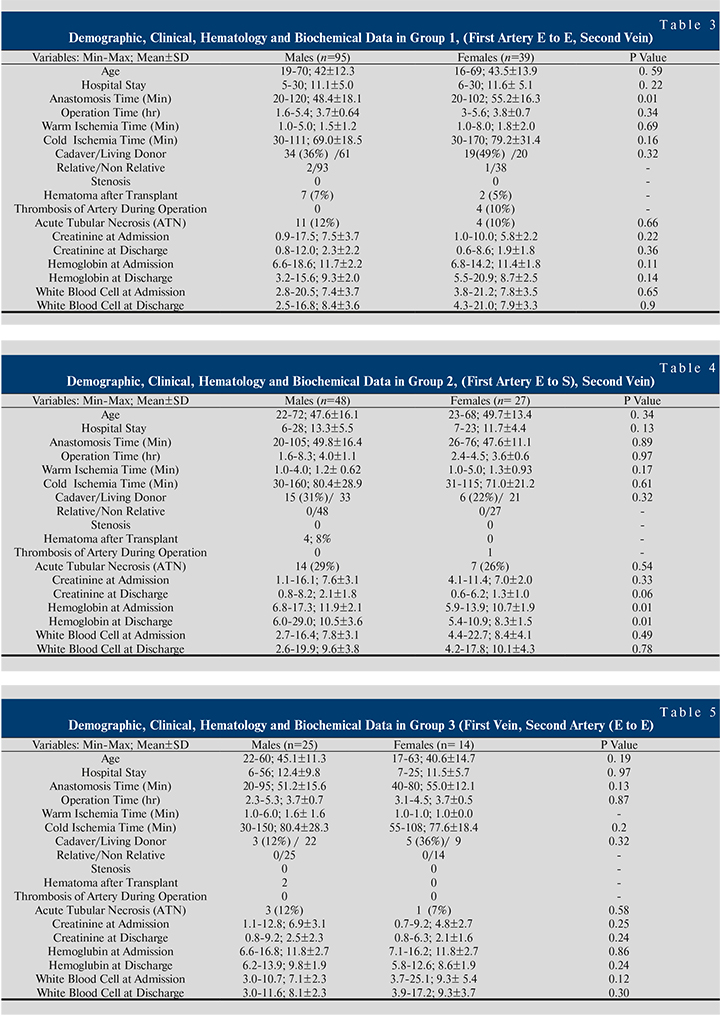

Table 3-6 shows demographic, clinical, hematological and biochemical data in groups 1–4. In the recipients that anastomosis performed based on FASV with end-to-end, the mean anastomosis time (minute) in females 55.2±16.3 was significantly higher than males 48.4±18.1 (p=0.01) (See Table 3).

In the recipients that anastomosis performed based on FASV with end-to-side, the mean hemoglobin at admission and discharge in the females was significantly lower than the males (p=0.01) (See Table 4).

Table 7 shows a comparison of data in groups 1-4. Comparison analysis showed for; anastomosis time (group 2 versus group 4; p=0.05), cadaver/living donor (group1 versus group 3; p=0.02), ATN (group1 versus group 2; p=0.002, group1 versus group 4; p=0.03).

Discussion. It is well known that surgical technique in the area of the renal vascular anastomoses is the critical part of transplant surgery. But there is not sufficient information regarding to preference and performance of anastomosis and its’ effect in kidney transplanted recipients. Therefore, this study was designed to provide data regarding to preference and performance of vascular anastomosis in kidney transplant recipients.

In agreement with previous publications, in this study with a minimum of 16 and a maximum of 72, the mean age of recipients was 45.0 years old. However the survival benefit of transplantation reported to be most obvious in younger ESRD but patients of all ages expanded further years of life with transplant compared with dialysis [17–22].

In this study the hospital length of stay (LOS) was with a median and a maximum of 10 and 56 days respectively. Publication in 2017 indicated that of; 173,868 kidney transplant recipients between 1995–2014, the median LOS was 5 days. In addition the prevalence of LOS exceeding 2 weeks decreased over time as by 2014, only 5.4% were hospitalized for 2 weeks or longer [23]. In this study the LOS in the 20% was between 16–30 days. However anastomosis time could effect on both graft and patient survival, in this study the median anastomosis time was 50 minutes in which in the 78% it was <60 minutes. A median anastomosis time of 36 minutes was reported in 2015 [24]. As organ shortage represents one of the major limitations to the development of kidney transplantation [25], and allografts from living-related donors have superior graft function and survival compared with cadaver allografts [11–17],in this study kidney obtained from a cadaveric donor in 33%.

There are conflicting data regarding to anastomosis based on FASV or FVSA. The end-to-end internal iliac artery anastomosis can be associated with complications due to compromised distal vascular supply to limbs and penile erectile tissue [26]. A method of end-to-side anastomosis can overcome them. Previous publications confirmed impression regarding to outcomes of kidney transplantation in vascular anastomosis technique based on FASV due to;1) delicate manner associated with better area for renal artery 2) maintain the kidney allograft in one position in addition to less manipulations that reduce the error of vessel twist. Furthermore, during the vascular anastomosis, repositioning of the kidney allograft is needed if the approach is vein first [27, 28]]. In this study, the preference of vessel anastomosis was based on FASV in 80%. Previous publication confirmed that the best technique regarding to renal artery anastomosis in terms of end-to-end to the internal iliac artery or end-to-side to the external or the common iliac arteries, is debatable even now. The results of both techniques are similar with one exception regarding the post-operative development of erectile dysfuction, which was higher among patients with end-toend anastomosis to the internal iliac artery. Both techniques has comparable surgical and clinical complications, without differences in graft and patients survival [20]]. Study performed by Pal DK., in 2017, in 20 patients with end-to-end and 20 patients with end-to-side anastomosis confirmed that end-to-side technique can be applied for renal transplantation, with some advantages over end-to-end technique, and without compromising efficacy [26]].

In this study in those with FASV end-to-end the mean anastomosis time (minute) in females (55.2) was significantly (p=0.001) higher than in males (48.4). In addition anastomosis time was shorter in FASV end-to-side (49) when compared to FVSA end-to-side (52.5). In the recipients that anastomosis performed based on FASV with end-to-side, the mean hemoglobin at admission and discharge in the females was significantly lower than the males.

Hematoma and acute tubular necrosis (ATN) was recorded in 5% and 18% that in 47% and 57% was associated with deceased donor. Sutherland RS et al., in 1993 showed that implantation into the internal iliac artery gave rise to higher risks of atheroma and endarterectomy [4]. In this study ATN was significantly lower (p=0.002) in FASV with end-to-end technique (11.2%) when compared to FASV (28%) with end-to-side technique. A 33% of ATN was reported in FVSA with end-to-side technique. Most transplant centers have a preffered technique using end-to-end anastomosis to the internal iliac artery, as facing with problems such as post-operative renal artery stenosis is more difficult with the end-to-side anastomosis due to the angle of anastomosis, although there is a greater probability of progress of «Steal phenomenon,» which could cause weakness in renal flow through exercises. In patients who underwent the end-to-end renal artery anastomosis technique to the internal iliac artery, erectile dysfunction was more frequent post-operatively. In theory, the reduction in blood supply to the pudendal artery arising from the internal iliac, even in the nonappearance of related vascular problem, to some extent declines the blood flow to the penis however without negatively affecting the potency [19–29].

Conclusion. Despite the higher use of deceased donor in recipients, those with surgical vascular anastomic technique based on FASV (end-to-end) showed the lowest rate of ATN (11.2%) when compared to other techniques. With the increase use of cadaveric donor, innovative management of vascular anastomoses in kidney transplantation seems to be a significant challenge. Further investigations in this area of kidney transplant surgery seem to be advantageous.