Introduction. Urolithiasis is derived from Greek word meaning urinary stone [1]. Over the past several decades, there has been a significant increase in the prevalence of nephrolithiasis in the general population [2]. Renal colic accounts for about 1% of all emergency department visits and 1% of hospital admissions. In approximately 95% of the patients, renal colic is caused by stones [3]. The introduction of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) and ureteroscopic stone extraction or disintegration (URS) for stones in the ureter has made open surgery unusual and, in the majority of cases, unnecessary [2]. Ureteroscopic lithotripsy is an effective technique in the management of ureteral stones [4]. Ureteroscopy occupy an essential place in the treatment of ureteric calculi as increasing technologic advancements allow easier access to stones in all parts of the kidney and ureter [5]. The improvements in ureteroscopic equipment emphasize the need for appropriate and effective miniaturized intracorporeal lithotripsy devices [6]. Ureteral stent placement has become a standard procedure after ureteroscopy since 1967. Indications include the reduction of complications after endoscopic surgery, although there is no clinical evidence for this [4]. More recently, stents have often been used to prevent complications after ureteroscopy, although this is controversial. Many ureteroscopic lithotripsy procedures are uncomplicated in that they cause no ureteral trauma and leave minimal or no residual stones, and thus the routine use of ureteral stents is considered unnecessary [4]. Ureteral stents are used for both the prevention and treatment of ureteral obstruction following ureteroscopy [6]. Laser is an acronym for light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation, The Holmium: Yttirum, Aluminum, Garnet laser (holmium: YAG laser) was developed in the early 1990s [7]. The holmium: YAG (Ho: YAG) laser is the newest wavelength device available for urological applications. Investigational work for lithotripsy with the Ho: YAG laser dates back to 1990 and clinical use began in 1993. The holmium laser has dramatically improved intraluminal lithotripsy and has become the intraluminal lithotripsy energy of choice for most urologists. It has a wavelength of 2,100 nm, which is absorbed in 3 mm of water and 0.4 mm of tissue, making it very safe for use in urology. Fragmentation of calculi is produced by a photothermal reaction with the crystalline matrix of calculi. Stone Retrieval Devices These include a variety of stone-graspers and baskets, electrodes, cup biopsy forceps, and intraluminal lithotripsy devices [8].

Patients and Method.

Patients and Method.

Design: prospective observational study

Setting: Urosurgical Theater in Al-Jumhoori Teaching Hospital, Mosul

Period: from 1st of January 2013

Sample Size: 200

Inclusion Criteria: All age group of both sex who present with ureteric stone and treated by ureteroscopy in urologic department.

Exclusion Criteria: Those have renal or bladder stone will not be included, also, those have ureteric stone not treated by ureteroscopy will be excluded

Intervention: observational Study; the data will collected according to especial questionnaire form which include: the need for stent insertion, the usage of laser lithotripsy, need of other ancillary equipment in ureteroscope, problems encountered during procedure.

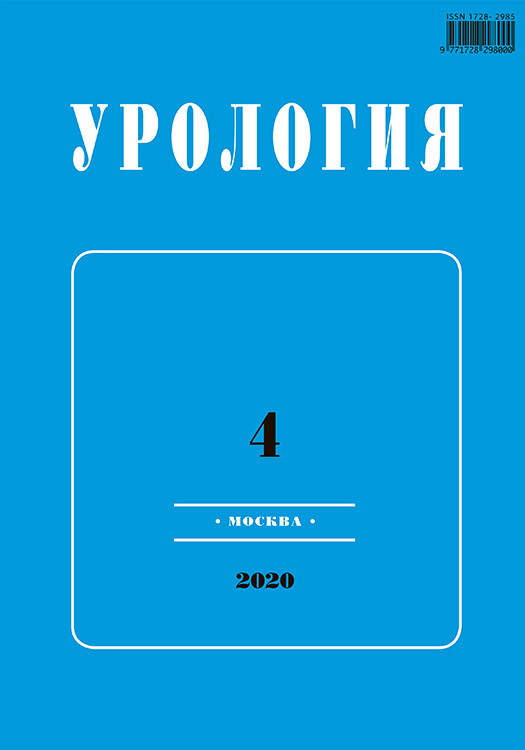

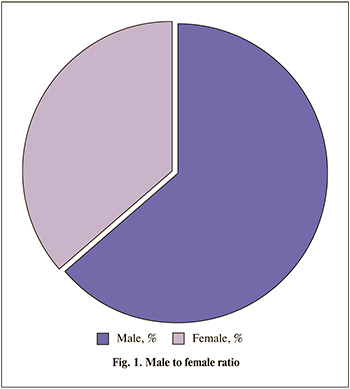

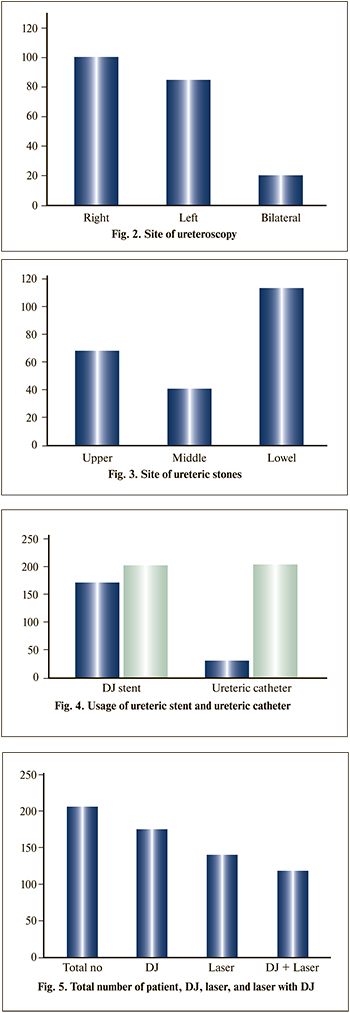

Results. During the study period, 200 patients were treated by retrograde semi rigid ureteroscopy for ureteral calculi. The study included 127 male and 73 female patients, (fig 1). Of the 200 patients, 159 came from urban area, while 41 patient came from rural area. Mean age of the patient is 36 years. Ureteroscopy had done in the right side in 98 patient, left side in 83 patient, and bilateral ureteroscopy in 19 patient, fig. 2. During performing the ureteroscopy, ureteric stones found in upper ureter in 86 patients, middle ureteric stone seen in 40 patients, and lower ureteric stone founded in 108 patients, 16 patients had stones at more than one location (upper, middle & lower) fig. 3. Ureteric catheter used in 33 patients, and had been removed after 48–72 hours, while Double J stent had been used in 175 patients and had been removed after 2 to 8 weeks Fig. 4. Double J usage distributed as following: Right side=73, Left side=84 while bilateral double J=13. Regard lithotripsy, the usage of holmium YAG laser for laser lithotripsy in 135 patients. Cases needed both laser lithotripsy and double J insertion was 112, fig. 5. Stone retrieval: Dormia basket used for stone retrieval in 50 patient, Forceps used in 23 case only (but there was technical problem during period of study, the forceps device was damaged). About 20 patients required second look ureteroscopy for clearance of residual stones, while the remaining patient the DJ stent were removed by simple cystoscopy without the need for ureteroscopy.

Results. During the study period, 200 patients were treated by retrograde semi rigid ureteroscopy for ureteral calculi. The study included 127 male and 73 female patients, (fig 1). Of the 200 patients, 159 came from urban area, while 41 patient came from rural area. Mean age of the patient is 36 years. Ureteroscopy had done in the right side in 98 patient, left side in 83 patient, and bilateral ureteroscopy in 19 patient, fig. 2. During performing the ureteroscopy, ureteric stones found in upper ureter in 86 patients, middle ureteric stone seen in 40 patients, and lower ureteric stone founded in 108 patients, 16 patients had stones at more than one location (upper, middle & lower) fig. 3. Ureteric catheter used in 33 patients, and had been removed after 48–72 hours, while Double J stent had been used in 175 patients and had been removed after 2 to 8 weeks Fig. 4. Double J usage distributed as following: Right side=73, Left side=84 while bilateral double J=13. Regard lithotripsy, the usage of holmium YAG laser for laser lithotripsy in 135 patients. Cases needed both laser lithotripsy and double J insertion was 112, fig. 5. Stone retrieval: Dormia basket used for stone retrieval in 50 patient, Forceps used in 23 case only (but there was technical problem during period of study, the forceps device was damaged). About 20 patients required second look ureteroscopy for clearance of residual stones, while the remaining patient the DJ stent were removed by simple cystoscopy without the need for ureteroscopy.

Discussion. The routine use of stent after ureteroscopy is somewhat debatable. Weinberg ET al. recommended keeping ureteric catheter for 24 to 48 hours after the procedure to prevent colic and to allow minor mucosal perforation to heal [9]. Others have recommended the use of stent to prevent long term complication and to decrease postoperative morbidity [10]. We have placed stents in ureteroscopy patients as some ureteric oedema causing upper tract dilatation and dysfunction is expected. Ureteric catheter was placed for 24 to 72 hours in all patients. JJ stents for approximately 4 weeks were kept in patients with impacted calculi and in patients with prolonged duration of procedure or mucosal injury. It has been show that JJ stents do not necessarily improve the results of ESWL [10]. The insertion of stents not only incurs an additional expense, but also is an invasive procedure associated with complications [11]. Ureteral stenting after ureteroscopic lithotripsy is a common practice to prevent postoperative complications such as ureteral obstruction. It was reported that uncomplicated URS can be performed without routine stenting with minimal patient discomfort and a low incidence of postoperative Complications [12, 13]. It was also reported that patients, in whom a stent was not inserted, were not at increased risk for complications and postoperative symptoms including flank pain after URS compared with those with a stent, and ureteral stenting after uncomplicated URS stone fragmentation was no longer absolutely necessary in all cases [14]. Routine stent placement has thus been questioned and the term ‘‘Uncomplicated URS’’ has entered the literature. Recent studies suggest that stenting is not required in ‘‘uncomplicated procedures’’ [15, 16], but there is a lack of consensus in definition of this term. Ureteral perforation or mucosal damage, large stone size, proximal stone localization, solitary kidney, anatomical anomalies, age under 18, and BDUO were defined as complicated URS [17]. Perforation, mucosal damage, solitary kidney, and anomalies of the kidney are regarded as absolute indications for stent placement; however, other indications are relative [18]. Disadvantages of stent placement were higher cost, increased risk of irritative urinary symptoms, and morbidity due to re-cystoscopy. Operation time was insignificantly increased.